The Church Overcomes

The Church Overcomes

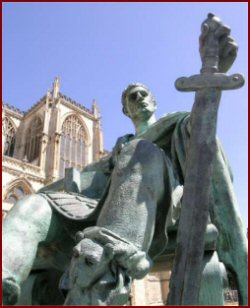

Constantine the Great at York

Constantine was proclaimed Emperor at York in 306.

- He overcame his rival in the West in 312 declaring his victory to be a result of an appearance of Christ to him in a dream.

- He reversed the Roman policy of persecution in 313.

- He became sole Emperor in 324.

- He moved the capital of the Empire to Constantinople

The consequences of these events were truly huge.

They resulted in a significant shift in the relationship between the Church and the power of sword.

The Anglo-Saxon Church at Richborough

The Roman legions left Britain in 410. The old picture of Britain smashed up by Anglo-Saxons and the Britons holed up in the wild western mountains is now seen to be overdrawn. Life went on: there is evidence that Britons continued as best they could in cities such as Bath, Wells, Chichester, Cirencester, Exeter, Gloucester, Winchester, Worcester, York, and Carlisle.

Even when the Anglo-Saxons, having been invited in as protectors, became invaders, the evidence that the church continued to thrive in eastern Britain is far stronger than was once believed. Silchester, Icklingham, Uley all suggest continuity between Roman Britain and Anglo-Saxon times. At Richborough, already noted for its baptismal pool, the old wooden chapel continued to be used. On the same site are the foundations of the Anglo-Saxon church.

In other words the ‘Living Tradition’ continued. It survived its first great political, social and cultural shock.

Extreme left, below the window, is the blocked Roman doorway;

in the middle of the picture is the new Saxon one

At Canterbury Bede says that a church outside the city, on the East side ‘was built while the Romans were still inhabiting Britain’ ‘in St Martin’s honour.’ Bede says this was the place ‘where the Christian queen’ (St Bertha) ‘went to pray. Here they first assembled to sing the psalms, to pray, to say Mass, to preach and to baptise, until the king’s (St Ethelbert) own conversion to the Faith gave them greater freedom to preach and to build and restore churches everywhere.’

It is with a real sense of awe that one enters St Martin’s. Roman tiles and stone are everywhere. In the chancel there is a small Roman Christian mausoleum, of which a wall and a doorway still exist. It is possible this was altered and enlarged to make a place of worship for Bertha and her chaplain. The making of a new doorway though the wall of the mausoleum can clearly be seen.

If the current St Martin’s had a Roman date this would make it the oldest church in continuous use in Britain.

When St Augustine was given the use of this building his monks added the chancel and nave.

St Pancras Church as it looks now

St Martin’s is an impressive place in its own right. But in truth there are two Roman churches outside and east of Canterbury. The problem with St Martin’s is that there was no Roman cemetery in the vicinity and so it could not have been a cemetery church. However the other church nearby, that of St Pancras, only 300 metres from the city walls, also built of reused Roman stone and tile, does have a Roman cemetery. As it turns out archaeologists found a Roman phase to this church: a coin of the house of Constantine (up to AD 337) was found close to the base of the wall. Maybe Bede’s material was not clear.

This church would have been a lot more suitable for St Augustine and his monks to use when they first arrived in Britain, and where perhaps, just outside the city walls, St Ethelbert of Kent was converted; in which case it is a church of great significance. Though it has inevitably undergone rebuilding it is still an impressive sight so close to the Anglo-Saxon Abbey of St Peter and St Paul which St Augustine and his 40 monks built for themselves.

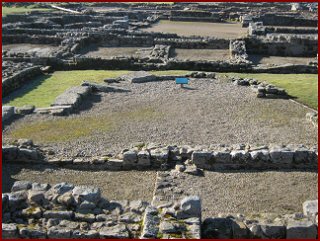

The Church at Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall

At the other end of the country, on Hadrian’s Wall, more churches have been found. A small church was built in the very centre of the Roman fort of Vindolanda, in the courtyard of the fort’s commander almost straight after the legions had left. This is a definitive statement that though the soldiers had gone, the Church was here to stay.

Also at Vindolanda a small portable altar was found with the Ch-Rho symbol on it – a smooth piece of sandstone, rather like a clay version of an Orthodox priest’s antimension. This too is a vivid testimony to the ongoing life of the church even in such far off places.

Llan(g)armon yn lal

After 380 a Briton named Pelagius taught distorted views of nature and grace in Rome and elsewhere.

In 429 and again in 447 St German of Auxerre along with Bishop Lupus of Troyes, was sent, perhaps by the Pope, to Britain to ensure that these views were corrected and removed. Their efforts seem to have met with success for nothing more is heard of the matter. He was evidently appreciated: the Britons in Wales and elsewhere dedicated several churches to him – as St Garmon.

The Picts came over the Wall

When the Picts came over the Wall and the Irish, Angles and Saxons conquered Britain and indeed much of Europe, they stood in awe of Empire: they sought its trappings and embraced its faith.

Christianity became the vehicle of carrying the Empire forward. The church utilised Roman places, Roman administration, Roman skills, Roman culture and Roman stones to build society and culture for a very long time.

But a new breed of Christian came into being. In the 5C monks were already arriving in Britain. With them new holy men, women and places also came into being.

The continuity of the Living Tradition was preserved.