Roman Britain

Roman Britain

Baptismal Pool at Richborough

Richborough in Kent was the great supply camp of the Roman army in Britain. As one stands there even now, surrounded by the great walls of the fort, we see inside a small tiled pit – a Christian baptismal pool!

Roman might and the call of Christ to sanctity, here in this spot is the perfect contrast between the Gospel and the world.

The Roman Empire

Within ten years of the Resurrection, the Romans arrived in Britain in AD 43 to stay. When Christians themselves arrived is a matter of speculation. The legends of Joseph of Arimathea and the child Jesus coming to Britain, or of St Paul or one or other of the apostles, or of a Christian king sending for missionaries in the 2C, do not inspire confidence. Even the often quoted text of Tacitus, the Roman historian writing about AD 200, suggesting that Christians had already arrived, is likely to be as much rhetoric as actual knowledge.

The beginnings were likely to be much more prosaic, soldiers, traders, artisans, even slaves, here and there, meeting in secret. The reason for secrecy was the same everywhere in the Empire: fear of persecution. We know nothing directly about these brothers and sisters.

Only one thing is clear: between us all, then and now, ‘there is one body and one Spirit, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all’. (Eph 4.4-6)

Icon of St Alban

Aidan Hart

The Christian church was a gift to the Empire because it was the only unified body in the whole Empire, the same everywhere from furthest East to furthest West. In turn the Empire was a gift to the church: for in it the church was able to manifest its own unity – in faith, ministry, sacrament and doctrine – in the face of all.

The Empire also united the church in the bond of martyrdom. In Britain it is reasonably certain three soldiers were the first to be martyred. There was St Alban who protected a priest. By all accounts he was beheaded on the hill where the cathedral of St Alban’s now stands, probably in the third century. A martyrium was built soon after. St Bede offers an account of St Alban’s trial; he also says that, St Germanus, Metropolitan Bishop of Auxerre in Gaul, came on an important visit to the country in 429, not longer after the Romans had left, and in the course of it visited the shrine and took some earth.

There was also St Julius and St Aaron, probably at Caerleon in South Wales. It is likely there were others.

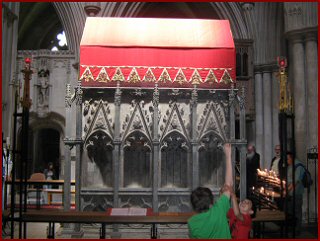

The Shrine of St Alban today

Jesus said ‘Take heart!. I have overcome the world’

Martyrdom has always been in the first rank of the ‘Living Tradition of the Saints.’ St Alban stood in the spiritual conflict between Christ and the world and allowed Christ to triumph.

But sanctity is rooted in created realities – his blood fell to the ground and a spring came up at the spot and that spring can still be seen.

The Saints are our intercessors. They can pray for this country in a way no others can.

St Alban is remembered in the Service of Preparation before the Orthodox liturgy.

We are called to stand with him in our time because the church in heaven and on earth is one; and because Christ has the victory over darkness, death and sin and this victory lies at the very heart of the Living Tradition.

St Athanasius

Wikimedia Commons

The church in Britain was everywhere normal, with bishops, councils, churches, priests, sacraments, and liturgy. Three bishops attended the church Council of Arles in Gaul in 314.

British bishops may even have attended that great Council in 325. A letter, found in Bath, was written to a lady named Nigra from a Christian called Vinisius who lived in Wroxeter, near Shrewsbury. He warns her of the arrival of a supporter of Arius whose teaching was the subject matter of the Council.

St Athanasius, the foremost proponent and defender of Nicea, in his Defence Against the Arians, refers to the Council of Sardica of 343 or 344, which decided against the Arians. He says, ’The sentence that was passed in my favour received the approval of more than three hundred bishops. He goes on to name the provinces from which these bishops came. The last name on the list is Britain.

By the end of the fifth century it has been estimated there may have been as many as 25 bishops in Britain. In 363 Athanasius wrote a letter to the Christian Emperor Jovian saying that ‘all the Churches in every quarter, both those in Spain and Britain, have assented to the Nicene Creed’. Britain was unquestionably Orthodox.

Praying the Liturgy

Stoa.org

Once Christianity had become the faith of the Empire, instead of meeting in homes, the bishops now built churches for public worship. They also built shrines for the martyrs; that of St Alban was well known even on the continent.

Six churches have been found so far from the Roman period: at Colchester (320/30); at Silchester near Reading (350); in London, at Tower Hill, there was a very large basilica (380); in Lincoln the church of St Paul-in-the-Bail, Westgate, may go back to Roman times. There may also have been a church at Lancaster, also at Uley in Gloucestershire and at Icklingham, in Suffolk.

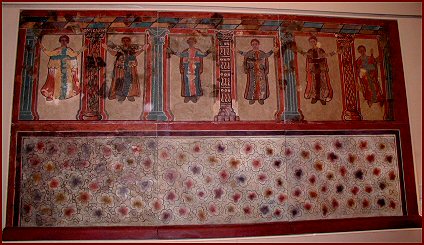

There were also house-churches. Britain has one of the oldest known in a private villa at Lullingstone in Kent. Most remarkably, somewhere between 363 and 378, a suite of rooms was adorned with Christian wall paintings and symbols. The main room was decorated with frescoes and between the pillars, were six painted figures, turned towards where the altar would have been. They had their arms outstretched – in the manner used by early Christians to pray – facing the east,

Christ, Hinton St Mary

British Museum

At a villa in Hinton St Mary in Dorset has the earliest non-symbolic representation of Christ in the Empire. It consists of a floor mosaic from the 4C showing Christ as young, fair-haired, and beardless. Behind him is the Chi-Rho sign. The mosaic, like the painting from Lullingstone, is now in the British Museum. Other mosaics, at Frampton in Dorset in a room with an apse dating from 4C shows a chalice and a chi- rho. Both of these places could have been ‘house-churches’.

Item from Water Newton

Wikimedia Commons

The earliest liturgical plate yet found in the Empire, consisting of 27 silver and one gold item, including vessels likely to be used for chalices, was discovered at Water Newton in Cambridgeshire. Some items are engraved with the Chi-rho symbol; another specifically refers to the ‘holy altar’ (or perhaps ‘holy church’). They date to 4C.

One item, a necklace, from a hoard found at Hoxne in Suffolk, also has a Chi-Rho symbol on it. It is likely to have been buried not long after the Romans left the country.

The picture given by mosaics and liturgical silver, along with the number of bishops and councils is no longer that of some impoverished group hiding in a corner. Christianity is out in the open for all to see.

Chi-Rho Lullingstone

British Museum

The picture of the church in Roman Britain is one of considerable vitality. Britain was fully equipped with all the elements of the ‘Living Tradition’. The usual picture of 3 saints and possibly 25 bishops is far too bald. It has been estimated that, even if only a fifth of the population were Christian, this would give us a figure of 10,000 Christians.

At some sites there are only a few stones to see. But let us always remember that we, along with all the saints, are ‘living stones’ ’ being built into a spiritual house to be a holy priesthood, offering spiritual sacrifices to God through Jesus Christ’. With the saints ‘we are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses’ . Such unity is present, alive and active, whenever the People of God gather together to celebrate the Liturgy

Alleluia!.