South Wales

South Wales

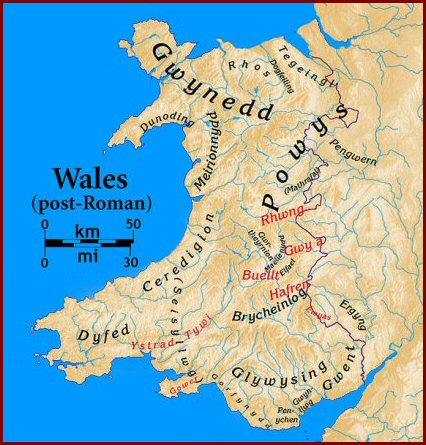

Early Kingdoms of Wales

Wikipedia.org

In Roman times Wales was much of a frontier zone. After the legions had gone, Britons continued as well as they could, but soon they were set about on every side by Irish, Scots and Picts. Many sought refuge in Wales, Cornwall, Brittany and Cumbria. With the reopening of the old western sea routes around the Irish Sea, people were able to come freely from Gaul, Spain, Africa and all ports east. Among them were monks.

Monks were a new phenomenon. In origin they go back to the virgins and ascetics of New Testament times. When the Empire became Christian, many in the Eastern and Western Mediterranean sought to live the Gospel to the full. They sought solitude in order to live in the presence of God through continual prayer. The coasts and mountains of Wales became monastic country.

The first monks arrived in Britain in the 5C, singly or in small numbers. The favour of the local chief was essential to their survival. If they obtained gifts of land they settled. They often choose old burial places, yews, and holy wells to purify them in the name of Christ. Islands were highly valued. But their oratories and cells were made of perishable materials. There is often nothing left of them but a name.

Icon of St Dyfrig

Aidan Hart

St Dyfrig (d 550) (Latin: Dubricius) was a bishop of the old Romano-British type somewhere in the region of Hereford and Gwent. He may have had some link with the great St Germanus of Auxerre (or with his disciples). He founded several monasteries and was an influential teacher; his disciples were St Iltud (llltyd) in the south and St Deiniol in the north. He made St Samson abbot of Caldey Island in the Severn Estuary and went there frequently. He also went to Brittany. He attended the Welsh Synod of Llandewi Breffi. He retired to Bardsey Island off the Lleyn Peninsula founded by St Cadfan. He died there. Sr Dyfrig was therefore of exceptional importance for the early church in Wales both in terms of the continuity of church tradition and as a unifying force. His tomb is in Llandaff Cathedral.

St Iltud (d 505) may havebeen a hermit at Llanilltyd Fawr (Llanwit Major) near Llandaff before building a monastery and school, said to have had hundreds of monks. He was called ‘the most learned of all the Britons’. He taught St David and St Samson and others, as well as making foundations in Brittany. He too was another key player in the early church in Wales.

St Teilo (b 500) was also influential not only in Wales but in Brittany. He founded a great monastery at Llandeilo Fawr. His tomb, and a relic of his skull. is also at Llandaff.

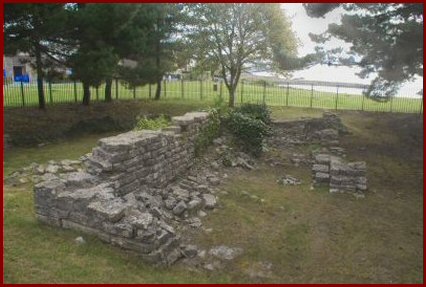

St Twrog’s Chapel

The old Post-Roman Kingdom of Gwent is rich in saints.

St Tathan (or Tatyw) (b 460) was an Irish monk who sailed up the Severn and founded a monastery in the middle of the old Roman town of Caerwent. He was known for his learning and called the ‘Father of all Gwent’. St Cadoc and St Malo (6C) trained under him.

St Cadoc and his disciples founded many monasteries. St Malo went to Brittany.

St Tewdrig (d 470) was a king of Brecon who became a hermit at Tintern. Recalled to fight when his people were in danger from the Saxons, he died of his wounds after the battle. He is buried in the church at Mathern and the holy well where he bathed his wounds is close by. This name preserves the word ‘merthyr’ i.e. martyr. The word was applied to several places in Wales of those deemed to have died for their faith.

Close to Mathern is an important crossing of the Severn. St Twrog (6C) (or some say St Tecla) built a hermitage on the small rocky islet just by the ferry on the western side.

St Docco founded a very early monastery at Llandough near Cardiff. There were other islands: Flatholm, where early graves have been found, and used by St Cadoc, and Steepholm used by St Gildas.

St Barruch’s Chapel

St Barruch (6C) lived on Barry Island on the Gower peninsula where a 15C pilgrim chapel has been recovered from the sands.

St Cenydd (6C) (Kenneth) also had a hermitage somewhere off the Gower; it could have been on the island of Burry Holms where a 6C chapel has been excavated.

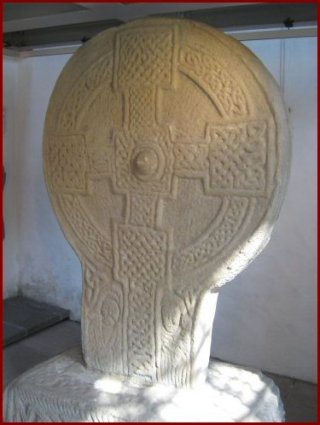

A fine Cross at Margam

There is nothing to see of an early monastery at Margam, Port Talbot; but several fine early crosses indicate conclusively there was one in the area. In 1147 the Cistercians founded an abbey there – and possibly used up the building stones. They survived till 1536.

The remote church of Kilgwrrwg

Saints and churches can be found in all sorts of out of the way places in Wales. The most remote church in Wales still in use is said to be that of Kilgwrrwg (pronounced Kilgoo-roo) in Gwent. It is a perfect example of an early Christian site, in this case of 8C, with a circular enclosure on the crest of a hill.

The current 12C church is tiny and almost completely hidden by the trees that surround it. It is now completely restored; of utter simplicity and still used. But in the 19C sheep were sheltered in bad weather in it and the droppings swept out before service on Sunday!

The interior now has an Orthodox icon of Christ and the Mother of God.

The altar is over the tomb

(with viewing grill from the church; and modern statue)

Partrishow, north of Abergavenny, under the Black Mountains, is another very remote place with a tiny church dedicated to St Issui (Isho or Ishaw). Everything about the location suggests he was an early hermit. His well will be found in a charming hollow by the roadside before one ascends to the church. Here is one of the few remaining ‘Eglwys y bedd’ (‘Church of the Grave’) left in Wales. An altar has been built over the grave. It is an astonishing place. Words are simply inadequate.

This has to be one of the great secrets of the Living Tradition in Wales

The Pilgrim Path up Slwch Tump

And who can pass by Slwch Tump? Brecon town, nestling amid its Beacons, has a small steep wooded hill in its western parts. St Eluned (Eilwedd), a virgin, was despised for her dishevelled appearance living a life of prayer. Her story is the classic one of a rejected suitor who found her and decapitated her. Her head rolled down the hill till it was stopped by a stone by a yew tree and a holy well rose on the spot. The Chapel and well are now gone but one can still climb the beautiful path up the hill under the trees which mediaeval pilgrims trod to reach them.

There are many stories of decapitated saints. The Celts thought heads were a special part of the human being. But in any case such a fate was an obvious way of quickly dispatching someone. Women were pretty defenceless. The appeal of such stories probably had much to do with the perversity of the male ego: ‘you cannot turn me down and expect to live’. To which the reply might be: ‘Now I am holy, you cannot touch me; and thousands kneel at my grave in remembrance of your evil deed’.

The famous Welsh historian Gerald of Wales lived in Brecon in the 12/3C; he was the archdeacon there. He personally testifies to the devotion St Eluned aroused and the conversions she caused.

She has a fine restored well at Llanddew, a little to the north east of Brecon town.

Caldey Island

In Dyfed, another of the old kingdoms, further west than the Gower, a monastery was begun on Caldey Island in 6C. The first abbot’s name was Piro. The Vikings destroyed it. But Benedictines set up an abbey there in the 12C. When that was destroyed at the Reformation, Anglican Benedictines re-established it in 1906, and, becoming Catholics in 1913, lived there until 1925. Cistercian monks took it over in 1929 and now form a thriving community.

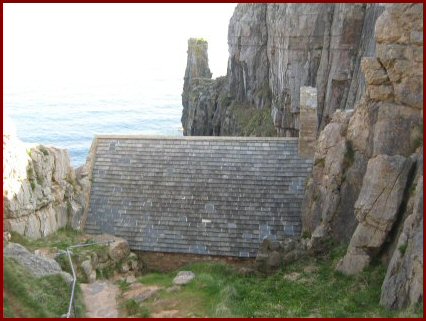

St Govan’s Chapel

St Govan (6C) was a hermit, possibly from Ireland just across the water, who found a tiny cave in the cleft of the cliffs south of Pembroke . This is an truly an astonishing and awesome place. A church for pilgrims was built over the opening of the cave in 11C, or even earlier. Words simply fail to describe the place. This site in all its simplicity speaks loudly of the Living Tradition.

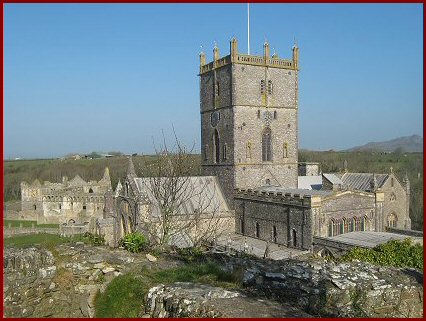

St David’s

St David (Dewi/Dafydd) ( b 487) founded an austere monastery very reminiscent of the Desert Fathers in a small hidden valley at St David’s in Pembrokeshire. The monks tilled the land, pulling the plough themselves without animals; they ate their bread with salt and herbs and water only, and that only at evening time. They prayed for much of the night.

The cathedral tower gives a great sense of stability and tranquillity to the place. The bones in his shrine may be those of St Caradoc a 12C hermit.

St Non’s Holy Well

Not far away a chapel on early foundations, and holy well, are dedicated to St Non, St David’s mother.

Pembrokeshire has at the very least some 236 holy wells.

St David was called the ‘Waterman’. He and his monks only drank cold water.

Ramsey island

St Justinian, a 6C hermit, possibly from Brittany, lived on Ramsey Island just off the coast of St David’s. A 14C pilgrim church, also built on early foundations, lies opposite the island on the mainland.

Christ Pantocrator at Llanwnda

North of St David’s is Llanwnda where St Gwyndaf (6C) of Brittany lived near the cliff at Strumble Head.

Several cross slabs, some of which may date to 7C suggest there was an important monastery here. One of the slabs is this very interesting and unusual: a Christ Pantocrator with Cherubim.

St Brychan’s Church Nevern

To the north east of St David’s is the church of St Hywel, brother of St Gwyndaf. A 5/6 gravestone proves its early foundation

Further north still, St Brynach (5/6C) founded his monastery at Nevern an important ancient religious centre. There are 5C gravestones carved in Latin and Ogham (an early Irish form of writing) and a 10/11C cross, possibly the finest in Wales. The church is surrounded by ancient yews, one of which ‘bleeds’. The short tower gives an impression of immense strength and peace.

Llandewi Brefi

6C British/Welsh leaders and priests were castigated by St Gildas for their ‘wicked’ ways, blaming them for the dire state of the ‘Britain’ in the face of the Saxons.

St Gildas’ views however seem to be very one-sided and histrionic, and give little or no detail.

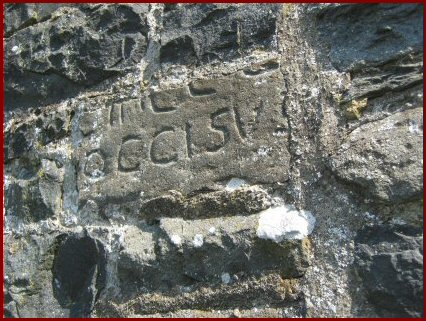

To be sure the Britons were in a bad state. But the Synod of Llandewi Brefi (’David’s church by the river Brefi’) in Cardiganshire that was (now Ceredigion) about 545, attended by St David, St Dyfrig and other early leaders suggests the church was pulling together and getting its house in order

In the church are some early Pillar Stones. Set in the outside of the church wall is an inscription which may well date back to 6C and may in its unbroken form have mentioned David.

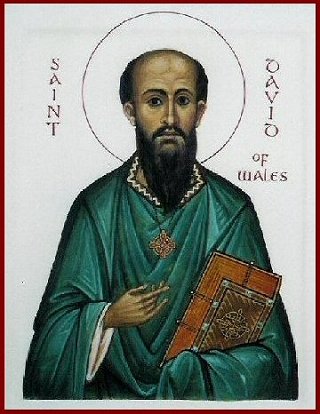

Icon of St David

Aidan Hart

South west Pembrokeshire is a ‘sacred landscape’ with its focus on St David. The churches, hermitages, ancient grave stones and holy wells, all came to be viewed in a unified landscape seen through the eyes of the pilgrim. The pilgrim looks beyond what passes away; he seeks the Kingdom of God, he looks for the heavenly city which is and which is to come. He meets with saints and angels and is lifted by them.

For the pilgrim this experience changes his life.

This experience of the unity of heaven and earth, of Christ and all his Saints together, of the cosmos as one, is celebrated in every liturgy.